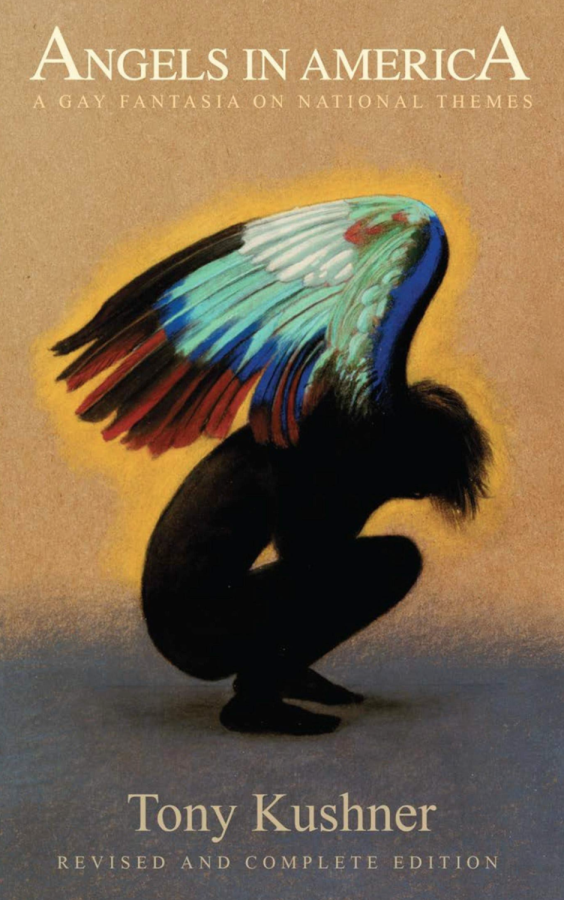

“Angels in America” is an Essential Text of Forgiveness

What Tony Kushner’s end times AIDS parable has to say about a crazy today.

“The world only spins forward,” says Prior Walter in the final lines of Tony Kushner’s Angels in America. For contemporary high schoolers reading Kushner’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play—which explores topics such as HIV/AIDS, queer rights, and discrimination in 1980s New York City—Prior’s assertion may be difficult to believe.

As teenagers like myself approach adulthood in the increasingly divisive political landscape of the 2020s, many of us feel that the world has begun to spin backward. Current research supports the anecdotes: In 2021, market research firm Dynata polled 604 American teenagers for the New York Times and found that less than half of respondents who were Black, Hispanic, Native, or Asian-American agreed that the government had their interests in mind. Political scientist David Campbell conducted a similar study in 2020 and found a “great disillusionment in democracy” among adolescents.

Amid Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine, the world’s democratic institutions appear all the more fragile, like matchsticks ready to be smoldered in Vladimir Putin’s fiery nostalgia for the Soviet Union. It is precisely in crises such as this one that educators should turn to Angels in America to deliver a lesson of moral clarity to their students.

Since Putin’s initial large-scale assault on Ukraine on February 24, some mainstream Western coverage has contributed to racial stereotypes about contemporary warfare. For instance, Charlie D’Agata, a CBS foreign correspondent in Kyiv, said on February 25 that the war in Ukraine is shocking because the country is “relatively civilized” and “relatively European” as compared to Iraq and Afghanistan. Such rhetoric reveals that Western reporters—particularly white correspondents of European descent—are desensitized to war that victimizes people who don’t look like them. In Kushner’s Angels in America, big-shot lawyer Roy Cohn exhibits this same detachment from tragedy when he is diagnosed with AIDS. Although Roy has sexual relationships with men, he refuses to call himself gay and openly displays homophobia. Ultimately, Roy’s selfishness and detachment from his own identity influence him to hoard AZT, a life-saving but extremely scarce drug for the disease. In this sense, just as reporters separate themselves from “typical” victims of war and thus perpetuate stereotypes, Roy so successfully alienates himself from gay men that he actively harms them.

While Roy represents the wickedness of such delusions, Belize, Roy’s nurse, demonstrates how we can best combat them: with forgiveness. Although Roy unleashes the full extent of his prejudice on Belize—a black and queer individual—Belize still treats Roy medically to the best of his abilities. After Roy’s death, Belize reflects that “He was a terrible person. He died a hard death. So maybe…a queen can forgive her vanquished foe. It isn’t easy, it doesn’t count if it’s easy, it’s the hardest thing. Forgiveness… Peace, at last.” Through Belize, Kushner teaches us that forgiveness is essential to our own “peace,” suggesting that even the worst people such as Roy Cohn are worthy of forgiveness. For high schoolers who are growing increasingly disillusioned with democracy, this is an essential message to heed—just as Belize forgives Roy for his bigotry, we must hold individuals such as news reporters accountable but ultimately forgive them. And where else in literature will we find such a clear message of forgiveness as that of a black, queer nurse absolving an intolerant lawyer-turned-murderer? Indeed, Angels in America is singular in its determination for forgiveness, making it an integral text in high school curriculums across the country.

Moreover, Kushner suggests that forgiveness and peace will always prevail, a message that can provide high schoolers solace in the current political landscape. In the play, Prior Walter contracts HIV and his long-term boyfriend, Louis Ironson, ultimately leaves him because he is unable to deal with Prior’s illness. Although Prior resents Louis for abandoning him, he ultimately forgives Louis much as Belize forgives Roy for his prejudice. Symbolically, Kushner concludes the play with Prior, Louis, Hannah, and Belize sitting under the Bethesda Angel in Central Park. Notably, the Bethesda Angel is a national symbol of health, purity, and peace, suggesting that the characters’ ultimate ability to overcome their differences will only serve them well. As high schoolers reckon with the current warfare in Ukraine, Angels in America can therefore provide optimism that peace and forgiveness will ultimately prevail in various forms.

“We will be citizens,” asserts Prior at the end of the play, speaking of gay men or perhaps of a broader coalition of marginalized people. In recent years, high schoolers have witnessed this same assertion of citizenship—of humanity—in several instances, such as during Black Lives Matter rallies and now the war in Ukraine. Through Prior and Belize’s forgiveness, Angels in America gives us hope that this humanity cannot be taken away; it allows us to conceive of a better world.