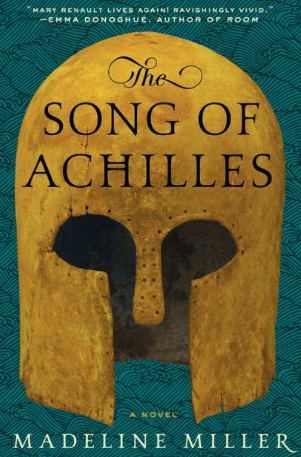

It would be a lie to say that I did not grasp the greatness of the book I had just picked up when I stumbled upon Madeline Miller’s The Song of Achilles. Its title and cover alone were enough to draw me in; yes, I judged a book on its cover, and I think in this case I judged well.

The title immediately piqued my interest, as I have long been a fan of Homer’s the Iliad and the Odyssey, and especially of my favorite Homeric character: Achilles, the ireful and golden warrior whose name occupies the first line of the Iliad. Additionally, the first part of the title caught my eye, as the Iliad would have been sung in ancient Greek times, so the reference delighted me and demonstrated the fact that the author understood a lot more about Homer than merely the expressions “long-haired Achaeans” and “wine-dark sea,” which I have found displayed unceremoniously in many contemporary retellings of Homeric tales.

My admiration for the novel only increased as I read it the first time…and the second…and the fifth. The Song of Achilles follows Patroclus, a secondary character in the Iliad. It suggests that he and Achilles are lovers, a theory over which much discourse has continued over the centuries. Spanning about twenty years, the novel first charts Patroclus’s lonely childhood and exile from his country due to a crime he didn’t intend to commit; as a result, he is brought to live with King Peleus of the Myrmidons, Achilles’s father.

Spending time together, they become best friends as well as lovers, and Miller approaches their love with fearlessness and sophistication, as she approaches all of the themes of the work: violence and anger, destiny, love as the opposite face of death and despair, and what makes someone “Aristos Achaion,” or “the best of the Greeks.”

The last portion of the book chronicles the Trojan War from Patroclus’s perspective, detailing the gore and glory as well as tender moments between himself and Achilles, moments charged with sweetness but also with the knowledge that Achilles, due to a prophecy he once received, faces death at Troy.

I cried at the end, despite knowing from the Iliad that Achilles must die. In my opinion, a great book can be read over and over and felt with the same emotion each time, as if the reader hopes that the ending will turn out differently. The Song of Achilles is one such story

The Song of Achilles is filled with just enough fascinating secondary characters, such as sparklingly gauche Diomedes of Argos, hotheaded Agamemnon, and the sweet captive girl Briseis, who falls fruitlessly in love with Patroclus. I particularly appreciated Miller’s treatment of the character Odysseus, whom she crafts with utmost detail, down to the scar on his foot and calf mentioned in the Odyssey.

In addition to a heart-wrenching story of love and adventure as well as an array of scintillating characters, the novel is one of my favorites due to Miller’s cleanly pressed prose, spare in parts and gloriously descriptive in others but always euphonious, as if her writing itself sings.

As Gregory Maguire aptly put it, Miller writes “with the confidence of the zealously inspired.” As professed by Miller, Patroclus is but an “ordinary” man, yet his story is one that can inspire anyone who reads The Song of Achilles.

Miller herself stated that, “one of my explicit desires in writing this book was to make it so that readers didn’t have to know anything about the Iliad to enjoy it.”

Although I approached it from the angle of already loving Homer, many friends and family members upon whom I have forced this book (and yes, they have all loved it) and who have not previously read Homer still loved The Song of Achilles, a story that has more to do with love and the struggle for morality—an ancient and ceaseless war—than with any particular fight.

In writing The Song of Achilles, Miller hopes to answer the question: “what does it mean to try to be an ethical person in a violent world?” The inquiry is a good one, and one we could all learn from. What indeed does make a person ethical when faced with such darkness and dolor?

Perhaps we should look toward Patroclus, an “ordinary” men, yet the true “Aristos Achaion,” to find the answer.