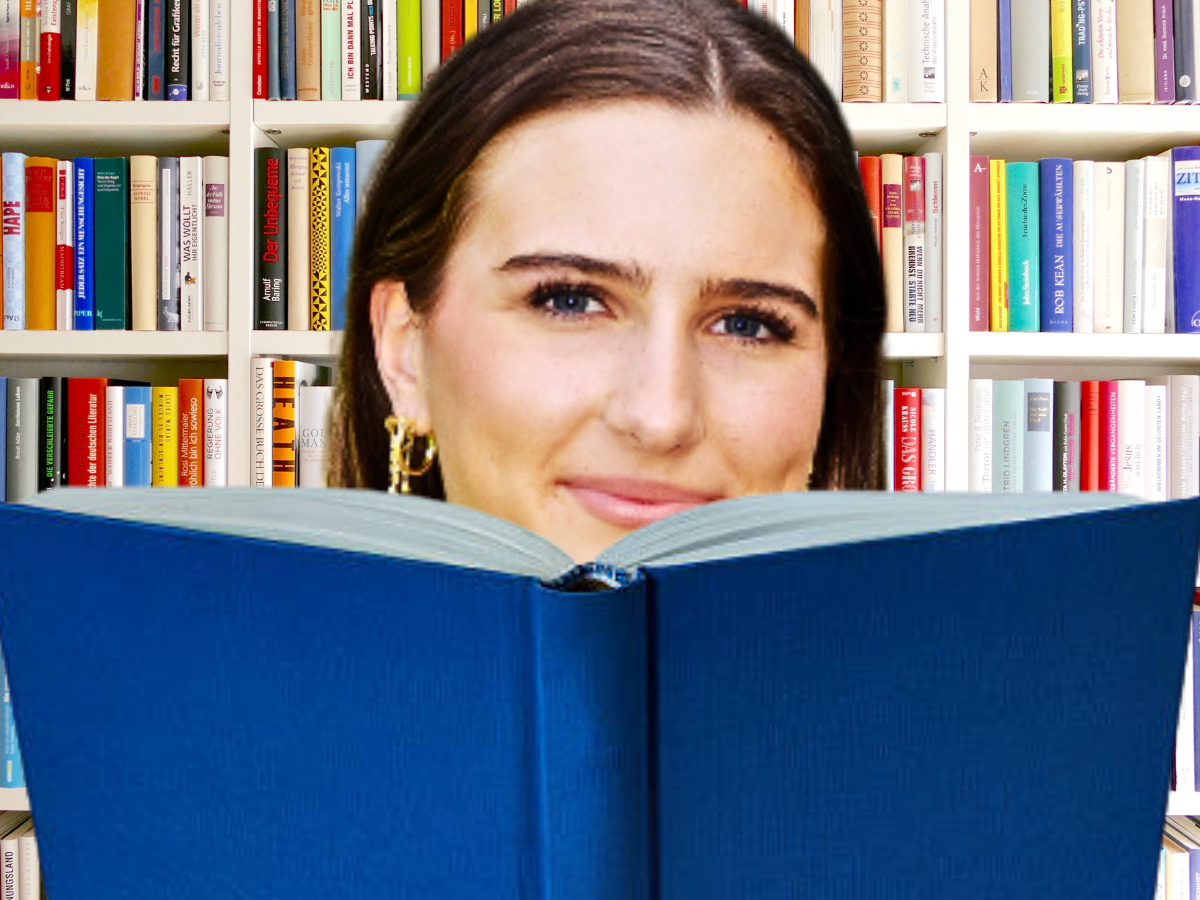

Massey theater rumbled in disbelief when Lauren Groff announced that she read approximately 300 books per year. However, the arguably more impressive aspect of Groff’s visit was her speech.

Lauren Groff opened the assembly with a witty and inspirational story about growing up as a perfectionist adolescent. She shared how, over time, she came to appreciate that the human inability to be perfect is truly beautiful. The story held an obvious message: “It is okay to fail.” While some in the audience felt her opening echoed a typical senior voice or merely saying what she thought was expected in front of a group of high school girls, I would argue that a writer as talented as Groff had a more ambitious message in mind: one on the necessity of vulnerable creativity.

Groff told us that every story she writes poses a question to the reader. Later she explained during a post-assembly workshop that she only discerns the true question the story seeks to ask after several drafts. Therefore, I believe we should approach her visit from a writer’s perspective: What questions does she challenge us to ask about ourselves?

A recurring theme in her story was the idea of “play.” She emphasized playing as not only important but essential for mental development, arguing that it is through this anarchical creativity that we grow as individuals and writers. Groff employed the notion of childlike play to elucidate her writing process: “I try to write how I used to run as a child.” I imagine myself running as a child and see a short, passionate girl taking hasty, uncoordinated steps with a determined expression in her eyes and inevitable bruises on her legs. The thought that someone writes with such impulsive disorientation and adamant resilience is amazing. It embodies the same type of contradiction that Groff used to describe the state of Florida, dancing across the line between suffering and beauty.

Groff went on to explain her writing process, which involves handwriting multiple drafts, the first of which she never reads. She acknowledges that this approach is not for everyone, emphasizing, “there are as many ways to write as there are writers.” She encouraged the individuality that every perfectionist fears, citing Thomas Edison’s quote: “The light bulb was an invention with 1000 steps.” She approaches writing like an inventor, taking a thousand steps to develop a story. Through this perspective, it seems that failure is not simply ‘okay,’ but rather impossible. Perhaps Groff’s question to us asks if humans, whose beauty is derived from their imperfections and imagination, are even capable of failure?

Groff’s visit, with its blend of wisdom and wit, served as a reminder that, in both writing and life, it is often in our moments of vulnerability and unbridled creativity that we discover the true beauty between the lines of perfection.